We visited Chengde in July of this year. Chengde is about 3-4 hours northeast of Beijing by train in Hebei province, and makes a nice weekend outing. Chengde is located in a river valley with the Wulie River runing along the eastern edge of the imperial summer resort. Chengde's old name is Rehe (the Europeans called it Jehol) or Warm River after the hot springs and streams located inside the imperial resort.

It was hot and hazy when we arrived in Chengde, and as these picture below show, Beijing doesn't have a monopoly on pollution. In his book, Mapping Chengde: The Qing Landscape Enterprise (University of Hawaii Press), Philippe Foret says on p.99 that Chengde has seen an expansion of cement and ceramic factories as well as the building of a titanium processing plant and it shows. The first picture shows a bend in the Wulie river, along with all the residential housing going up in the city. I like the third picture because it shows the office building housing the Chengde Environmental Protection Agency (you can barely make out the Chinese characters) with a thick layer of smog covering the city behind it. Obviously, the Environmental Protection people have some work to do in cleaning up the air in this historic city!

Here's a picture of the entrance to the hotel we stayed in, the New Century Rehe Hotel. It's actually located inside a shopping mall and to get to our rooms, you had to go through this door and climb up a flight of dark stairs to the 3rd and 4th floors where the rooms were. Not highly recommended, but it was cheap, about U.S.$30 a night.

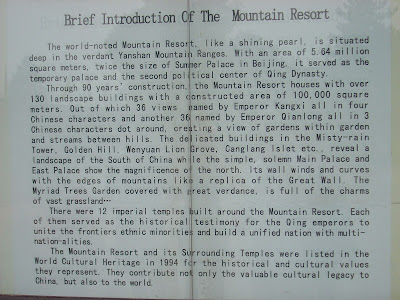

THE MOUNTAIN VILLA

After leaving our "hotel", we made a beeline for the central attraction: the imperial summer resort built by Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong, also known as Bishu Shanzhuang, which translates roughly into "Fleeing the Heat Mountain Villa". I assume the emperors were fleeing the heat of Beijing, and indeed it did feel cooler inside the villa due to all the trees. We entered the front gate, known as Lizheng Gate, shown here along with an introduction the villa.

Below is a map of the villa. The Lizheng Gate is down at the bottom. On the right hand part of the map (north and east), you can see the 8 Outer Temples (waiba miao) that we visit later. Note also the Wulie river running alongside the eastern edge of the villa, and the lake district on the lower right. To the north of the lake district is the prarie district, while to the west is the hill district. As Foret details in his book, each of these districts evokes different parts of the Qing empire: the lake district evokes the area of China known as Jiangnan, the prarie district is a reminder of the Mongolian plains, and the hill district evokes the northern frontier from which the Manchus originated.

The pathway through the Lizheng Gate leads to a series of 9 courtyards with 5 halls. The first hall is the Hall of Simplicity and Sincerity which was built in 1711 out of aromatic cedar as a place for the emperor to rest. One can imagine the Emperor Kangxi catching a quick snooze in that yellow throne while being serenaded by these musicians.

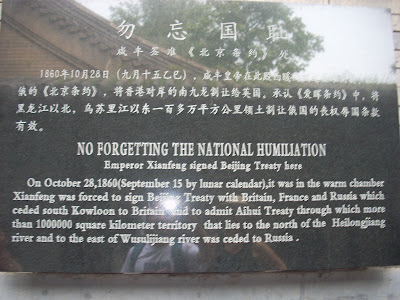

The Chinese never miss an opportunity to remind us of their national humiliation. Walking through the courtyards, I came across this sign. The signing of the Beijing Treaty was followed later that year by the burning down of the Summer Palace in Beijing by British forces. As we'll see, parts of this resort were also damaged by invading Japanese forces during World War II.

Emerging from the courtyards, you come out onto the Lake District which is supposed to evoke the landscape of the Jiangnan region in eastern China.

A footnote about the lake district. According to Foret (pp.51-52), there is a hill built here called Jinshan Hill (Golden Hill) that forms an important axis with Qingchui peak, otherwise known as Club Rock (see pictures below). Qingchui peak is supposed to have cosmological significance because of its parallel with the sacred Sumeru mountain in Buddhist cosmology. The problem with Qingchui peak is that it lies to the east of the 8 outer temples and thus lacks a central location in Chengde. Foret argues that this problem was solved by building Jinshan Hill (complete with temple) in the middle of the summer resort so that it runs in a straight line from Qingchui peak through the middle of Pule temple (one of the 8 outer temples). Jinshan thus substitutes for Qingchui peak in a central location and serves as a metaphor for Sumeru. Make sense?

Here are some naughty children feeding some sika deer which roam wild in the resort. There are signs telling people not to feed the deer or get close to them, but this being China, people usually tend to ignore the signs and do what they want.

One thing I didn't realize was how much this resort was used as a kind of public space. There are all kinds of people congregating here just hanging out, singing, doing their own thing. Here's a group of people singing and playing instruments while others sit and watch.

Walking north from the lake district, you come across the prairie district. We saw these yurts with a people standing around, so we took a peek out of curiousity. It turned out to be a touristy talent show with a "Mongolian cowboy" belting out some Mongolian folk songs. That was followed by a group of little girls dancing around in Mongolian costumes. Do I hear Genghis Khan turning over in his grave?

Walking north from the lake district, you come across the prairie district. We saw these yurts with a people standing around, so we took a peek out of curiousity. It turned out to be a touristy talent show with a "Mongolian cowboy" belting out some Mongolian folk songs. That was followed by a group of little girls dancing around in Mongolian costumes. Do I hear Genghis Khan turning over in his grave?

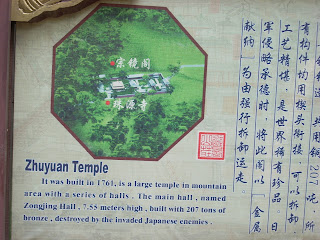

Walking west away from the Mongolian cowboy, we entered the hill district. This is a very large area, and we didn't have time to see much of it, but we did take in the Zhuyuan temple (or what was left of it) which was destroyed by Japanese troops during World War II. You don't usually get to see ruins in China because the Chinese are so efficient at reconstructing historical sites, so to see some actual ruins was a treat.

Walking west away from the Mongolian cowboy, we entered the hill district. This is a very large area, and we didn't have time to see much of it, but we did take in the Zhuyuan temple (or what was left of it) which was destroyed by Japanese troops during World War II. You don't usually get to see ruins in China because the Chinese are so efficient at reconstructing historical sites, so to see some actual ruins was a treat.

THE OUTER TEMPLES (waiba miao)

The following day, after a good night's sleep in our luxurious accomodations (did I mention we didn't have water for a few hours?), we took a bus to some of the outer temples that encircle the imperial resort.

Our first stop was Puning Temple, which I have to say is one of my favorite temples in China, and the only active temple among the 8 outer temples. According to Foret, Puning houses the local Buddhist association (the Communist Party supervises the Buddhist temples through these associations). (On a historical note, Foret on p.51 says that during the Qing dynasty, many of the 8 outer temples did not have a permanent religious community and were under supervision of the Imperial Household Court, while the clergy of some of the other temples were largely Mongols.) Surprisingly, no one else in our bus wanted to wander in, so we had to rush through the temple grounds while the rest of the group waited for us on the bus.

Puning Temple, also known as the Great Buddha Temple or the Temple of Universal Peace, is a blend of Chinese and Tibetan temple architecture. It was built in 1755 to commemorate Qianlong's pacification of the Zungar tribes in Xinjiang. While Puning is said to be modelled on the earliest Tibetan Buddhist monastery (Samye), it looks in many respects like many other Buddhist temples we've seen in China, although the rear portion of the temple grounds and the facade of some of the outer walls have some Tibetan influences. As Foret notes, the fusion of Chinese and Tibetan features was as much for Tibetan visitors to the Qing summer court as it was for Mongols who were themselves followers of Tibetan Buddhism. In this sense, as Foret notes on p.53, temple construction in Chengde served the Qing's policy of incorporating Tibetans and Mongols into its empire. One sees the incorporation of Chinese, Tibetan and Mongol themes in many of the Chengde temples.

When you first enter the temple, you are met by chubby Milefo, the Laughing Buddha (see picture on left), which apparently is typical of Lama Buddhist temples. Behind that is the Hall of Heavenly Kings housing three images of Buddha. But what takes your breath away is the next

hall, the very tall and elaborate Mahayana Hall (see picture on the right) which houses one of the most beautiful Buddhist statues of Guanyin Buddha (the Goddess of Mercy) anywhere. The golden statue is 22 meters tall and made out of 5 different kinds of wood: pine, cypress, fir, elm, and linden. The statue shows Guanyin with 42 arms, with each palm bearing an eye and each hand holding an instrument, skulls, lotuses, and other Buddhist devices. Unfortunately I was not allowed to take a picture of the statue. You'll just have to take my word that it was a sight to behold.

hall, the very tall and elaborate Mahayana Hall (see picture on the right) which houses one of the most beautiful Buddhist statues of Guanyin Buddha (the Goddess of Mercy) anywhere. The golden statue is 22 meters tall and made out of 5 different kinds of wood: pine, cypress, fir, elm, and linden. The statue shows Guanyin with 42 arms, with each palm bearing an eye and each hand holding an instrument, skulls, lotuses, and other Buddhist devices. Unfortunately I was not allowed to take a picture of the statue. You'll just have to take my word that it was a sight to behold.

Going further toward the rear of the temple, I discovered a band of musicians and architecture with more of a Tibetan influence. Note the white block-like shapes, the stupas, Tibetan prayer wheels....

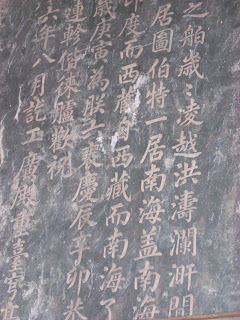

After Puning, we quickly jumped on the bus which took us to the temple that was on everyone's itinerary: the Putuozongcheng Temple, which is a miniature version of the Potola Palace in Lhasa. Foret (p.51) notes that this temple is the most important temple in Chengde in terms of size: it is ten times the average size of a Chengde temple. The temple was constructed in 1767-1771. It really is a beautiful temple although the views of the temple would have been nicer on a clear day. Here are some pictures of the entrance to the temple, followed by a large stele pavilion which has Chinese, Mongol, Tibetan and Manchu writing on it (see if you can guess which is which!), a triple archway topped with 5 stupas, the skull of a yak(?), and stone elephant whose knees are bent at a fantastical angle.

The most striking structure is the Red Palace which contains most of the main shrines and halls in the temple complex. Running down the front of the Red Palace are collections of prayer flags.

Here is a view looking westward from the Red Palace toward the hills encircling the imperial summer resort that we had visited the day before. One imagines that during the 1700s, the air was a bit clearer than what we experienced on this hazy July day in 2008.